The Pathophysiology Of Ischemic Stroke - The Function Of Aquaporins

In order for treatment design techniques to work, it is important to have a good understanding of the complex molecular and hemodynamic processes that are part of the pathophysiology of ischemic stroke. In many industrialized countries, stroke is one of the leading causes of death, and the number of strokes is slowly going up around the world.

Author:Suleman ShahReviewer:Han JuMay 29, 202345.6K Shares616.6K Views

In order for treatment design techniques to work, it is important to have a good understanding of the complex molecular and hemodynamic processes that are part of the pathophysiology of ischemic stroke.

In many industrialized countries, stroke is one of the leading causes of death, and the number of strokes is slowly going up around the world.

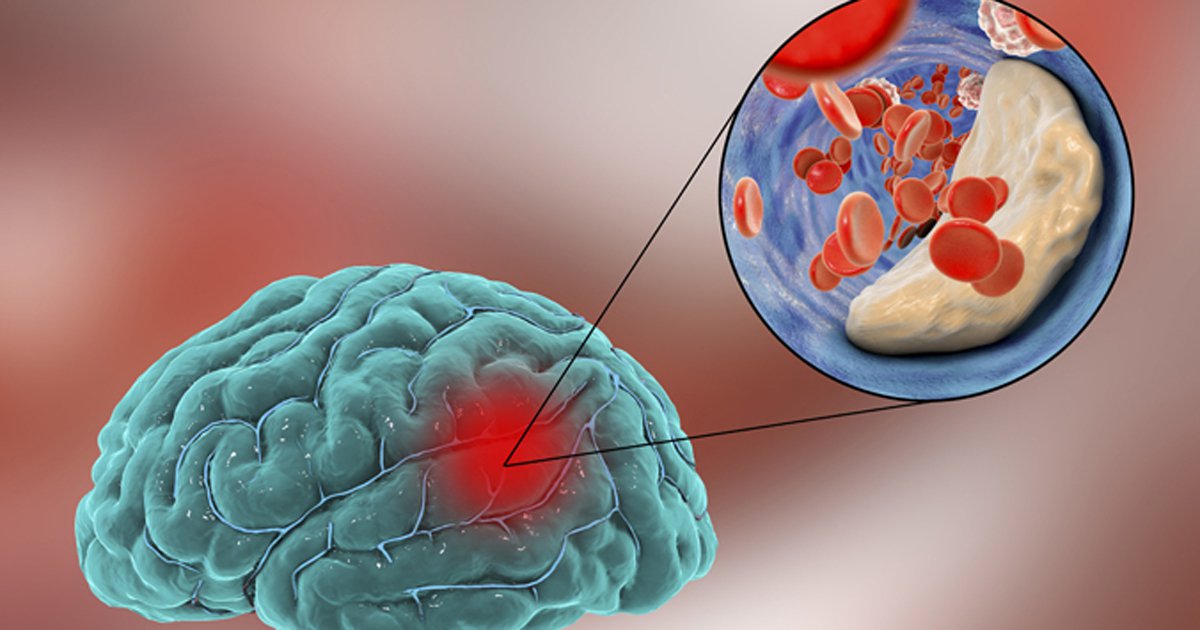

The most frequent kind, ischemic stroke, is responsible for around 85% of fatalities and happens when decreased cerebral blood flow brought on by abrupt or progressive artery blockage causes damage to a specific region of the brain.

At least three primary forms of the family of specialized water channels known as aquaporins (AQPs) are present in the central nervous system. They are expressed in diverse cell types.

They helped us learn a lot about how water is taken in and let out across different membranes, and their findings shed light on how water is distributed across the different parts of the brain.

They play an important role in physiology and a number of diseases, and they help maintain the water balance in the body.

Ischemic Stroke And Cerebral Edema

In the adult brain, water is distributed across cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood, intracellular, and interstitial compartments.

Osmotic gradients and hydrostatic pressure variations govern fluid transport between vascular, ventricular, and parenchymal compartments. Neurovascular cells (vasculature, neurons, astrocytes) govern water transport.

Iliff and Nedergaard's "glymphatic system" aims to define water transport through a paravascular route between glial and vascular cells that may contain unknown channels. Edema worsens ischemic stroke. Even minute changes in brain capacity raise intracranial pressure and compress neuronal tissue and vessels.

Edema affects stroke mortality and morbidity. Current treatments for cerebral edema include osmotic medicines like mannitol and surgical decompression, but they are not molecular.

Stroke Pathophysiology, Etiology and Risk Factors

Edema Formation In Stroke Pathophysiology

In ischemic stroke, edema generally peaks 24–72 h after the ischemic event and is followed by molecular and cellular neurovascular unit changes.

Ischemic cerebral edema may be pathophysiologically separated into an early cytotoxic form and a later vasogenic type after 4–6 h. Anoxic edema and ionic edema are newer types that focus on what causes edema rather than where it is.

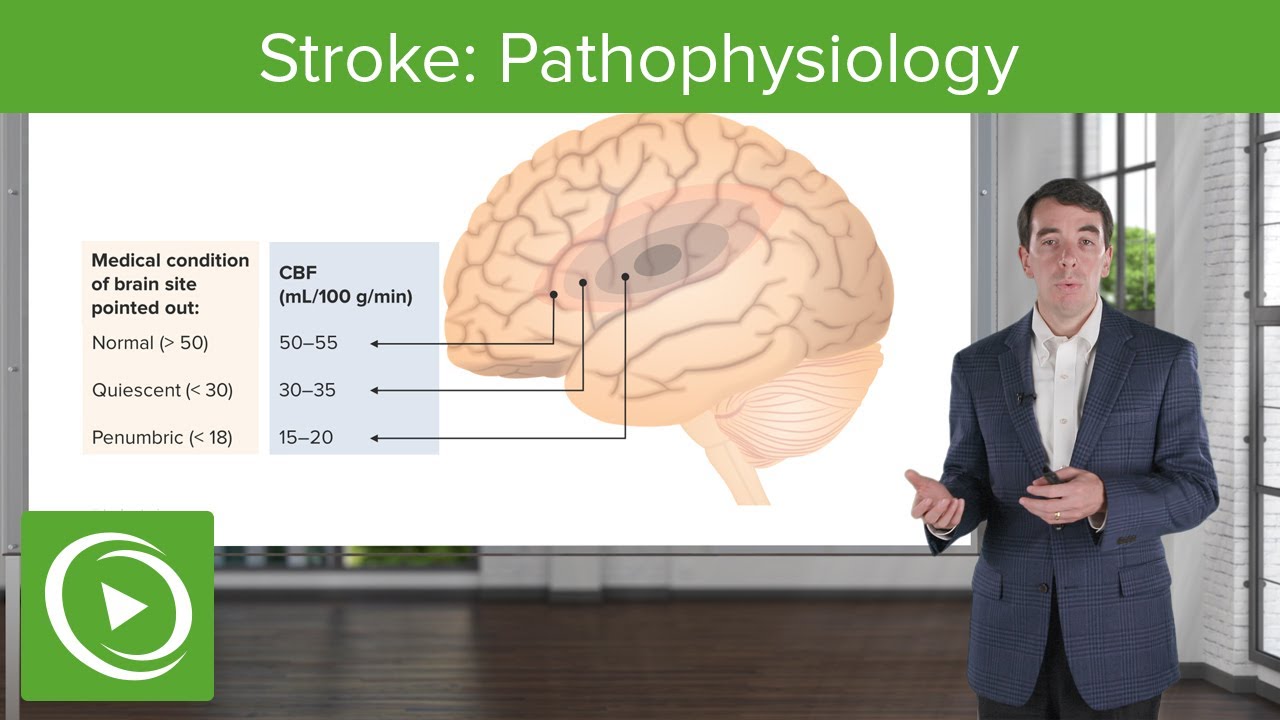

Ischemic edema has a vascular threshold-dependent temporal course. At ~30% perfusion, activation of anoxic metabolism promotes brain tissue osmolarity and cell swelling. At levels below 20% of control flow, anoxic depolarization and ionic regulation failure increase intracellular osmolarity and cell edema.

During this acute phase, tissue damage is caused by ischemia-induced energy failure and depolarization due to Na+/K+-ATPase and Na+ co-transporter stoppage. Ionic gradients are disrupted by intracellular ion buildup and reuptake failure.

Osmotic water input promotes astrocyte and dendritic enlargement and extracellular compartment shrinkage but not net water content. The fluid shift lowers the apparent diffusion coefficient of water, which makes the signal stronger in diffusion-weighted MR imaging.

Countering Edema

Under normal settings, edema is evacuated by the ependyma into the ventricular CSF, the glia limitans into the subarachnoid CSF, and the blood-brain barrier (BBB) into the blood. How much each one helps get rid of edema may depend on how big the barrier is and how much pressure is inside the brain.

Vasogenic edema is removed by the bulk movement of fluid via the extracellular space, through the glia limitans into the ventricles and subarachnoid space, and to a lesser extent by astrocyte foot processes and capillary endothelium into the circulation.

Albumin extravasation after BBB disruption promotes cerebral water and edema. Papadopoulos and colleagues showed in aquaporin 4 (AQP4)-null mice that AQP4-dependent transcellular water flow is important to the transfer of edema fluid through astrocyte cell membranes of the glia limitans into the CSF.

These results confirm Reulen and colleagues' observations that edema fluid moves toward the ventricle.

In human and rodent brain edema, AQP4 expression in astrocytes is altered. Interstitial edema severity was related to AQP4 upregulation, which might represent a preventive mechanism against edema buildup. Due to its role in getting rid of swelling, AQP4 expression going up could be a good indicator of how much water is in the brain.

Aquaporin Distribution In The Central Nervous System

In the central nervous system (CNS), AQPs connect the three main parts of the brain: the CSF space (which is made up of the cerebral ventricles and subarachnoid space), the brain parenchyma (intracellular and extracellular space), and the intraventricular compartment.

The majority of the AQPs in these compartments in mouse brains are AQP1 and AQP4. The CNS expresses just a portion of the 14 known AQPs, including AQP1, AQP4, and AQP9. Each kind of AQP expresses itself differently in different tissues, and throughout development, events like damage may change this expression.

The locations where AQP are expressed may also indicate the specific roles that each kind plays. Numerous human disorders have been linked to genetic flaws in aquaporin genes. The most serious effects are hereditary nephrogenic diabetesinsipidus and cataracts, both of which are caused by changes in the AQP2 gene.

Aquaporin 1, 4, And 9 - Where They Are Found In The Brain

Aquaporin 1 (AQP1) is expressed in the choroid plexus, which forms the barrier between CSF and blood. Except in circumventricular organs, it's missing in cerebrovascular endothelial cells. AQP1 is made by the ependymal cells that line the central canal and dorsal horn sensory fibers in the spinal cord.

Aquaporin 4 (AQP4) is the most prevalent water channel in the brain. It is found in astrocyte perivascular end-feet and glial limiting membranes at the brain parenchyma-subarachnoid CSF boundary and underneath the ependyma-brain parenchyma-ventricular CSF boundary.

Aquaporin 9 (AQP9) is an aquaglyceroporin that allows water, glycogen, lactate, urea, purines, pyrimidines, and monocarboxylates to pass through. AQP9 is expressed in the spinal cord, retina, and liver. AQP9 is distributed across astrocyte cell bodies and processes in the brain, unlike AQP4, which is found in astrocyte foot processes.

Stroke: Pathophysiology | Clinical Neurology

AQP4 Expression In Ischemic Stroke

AQP4 expression coincides with glial-specific edema and is geographically and temporally modulated by the stroke model.

In a mouse model of acute cerebral ischemia, AQP4 expression went up quickly in the end-feet of blood vessels. It reached its peak 1 hour after the occlusion, which was the same time as early cerebral edema.

Another rise in penumbra expression at 48 h was connected with cerebral edema. This may imply that AQP4 is the main water route following brief cerebral ischemia.

Early AQP4 expression was not found under models of strokes that were worse, like persistent distal MCAO. This shows that the brain can't make enough AQP4 proteins when things are bad.

Hypoxia-ischemia in young rats and 90-min MCAO showed different expression profiles. This key research indicated that spatiotemporal up-regulation of AQP4 depends on stroke model and type, species and age, and insult intensity.

AQP1 And Cerebrospinal Fluid

Due to its expression site, AQP1 may have a function in CSF secretion. CSF production is driven by Cl/HCO3 and Na+/H+ exchangers in choroid plexus basolateral membranes.

The high osmotic-diffusional water permeability ratio of the choroid epithelium may be due to AQP1 on the apical membranes, which points to an aqueous route.

In AQP1-null mice, choroid plexus osmotic water permeability is decreased five-fold. This reduces intracranial pressure by 50% and may affect ischemia. AQP1-null animals had a 25% lower CSF secretion rate than wild-type mice, proving it's not the only contributor. Using AQP1 mice, no one has yet found out what role this water channel plays in making CSF.

AQP1 expression in astrocytes is connected to CSF production, and its neuronal expression may be linked to neuroplasticity and repair (GAP-43). AQP1 is expressed in rat and human malignant brain tumor endothelium and reactive astrocytes.

This gene may increase tumor BBB water permeability. AQP1 on reactive astrocytes suggests a role in cell migration. The link between the two has not been studied.

In patients with ischemic stroke, hydrocephalus, or intracranial hypertension, AQP1 inhibitors may reduce CSF buildup.

AQP9 In Cerebral Ischemia

After acute MCAO, AQP9 is up-regulated in reactive astrocytes along the infarct border in mice, but mostly in the cortex, ventral pallidum, and amygdala nuclei, with a considerable induction after 24 h and an increase over time.

The highest level of expression was seen 7 days after a stroke, which suggests that it may have something to do with the growth of reactive astrocytes and glial scar tissue.

The identical geographical distribution of the up-regulated AQP4 suggests that both AQPs may be involved in the production of edema and water fluxes. However, no correlation between AQP9 and edema was discovered, indicating that AQP9 may play a bigger role as a metabolite channel in ischemia.

Contrary to AQP4, AQP9 is not polarized on the end-feet of astrocytes, and its pattern of expression is assumed to support a function in the Pellerin and Magistretti-proposed "lactate shuttle" concept. One of AQP9's main functions is thought to be the transport of lactate into mitochondria.

Ischemic lactic acidosis is deprotonated and helps to lessen the proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane when it is exposed to the comparatively high pH of the membrane. This concentration gradient makes it easier for AQP9 in mitochondria to take in lactate, and this effect is stronger in hypoxia-ischemia.

AQP9 may help neurons recover by making it easier for lactate to move between astrocytes and neurons and by making it easier for lactate to leave the energy-conserving system (ECS).

As a result, it is possible to interpret the up-regulation of AQP9 following ischemia as a cell survival strategy. This suggests a unique avenue for ischemic pre-conditioning. But no one knows exactly what AQP9 does yet, and research can't move forward because there aren't any better or more focused AQP9 antibodies.

People Also Ask

What Does Pathophysiology Of Stroke Mean?

A stroke happens when the blood supply to a portion of the brain is cut off, which causes some degree of long-term neurological impairment.

What Is The Difference Between An Embolic And A Thrombotic Ischemic Stroke?

A blood clot (thrombus) in a brain artery is what causes thrombotic strokes. A blood clot that has formed elsewhere (often in the heart or neck arteries) may move through the circulation and obstruct a blood vessel in or leading to the brain, resulting in an embolic stroke.

What Is The Mechanism Of Injury In Ischemic Stroke In The Brain?

Ischemic stroke is caused by an abrupt drop in blood flow to a portion of the brain, which causes a commensurate loss of neurological function. This general phrase covers a wide range of etiologies, including thrombosis, embolism, and relative hypoperfusion.

What Is The Most Common Cause Of Ischemic Stroke?

The more frequent form is ischemic stroke. A blood clot that stops or plugs a blood vessel in the brain is often the culprit. This prevents the brain from receiving blood flow.

Conclusion

Significant progress has been made in the understanding of aquaporins and their function in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke. Regulating water transport is a crucial component of treating ischemic stroke, so ongoing research is needed in the pursuit of understanding new processes that can enhance the course of this condition.

They are clinically very significant since they have the capacity to both magnify positive outcomes and decrease negative ones when used carefully at various stages of stroke. Last but not least, the development of new ways to find selected modulators with subtype specificity and affinity for certain AQPs is likely to lead to major advances in basic lifesciences and medicine.

Jump to

Ischemic Stroke And Cerebral Edema

Edema Formation In Stroke Pathophysiology

Countering Edema

Aquaporin Distribution In The Central Nervous System

Aquaporin 1, 4, And 9 - Where They Are Found In The Brain

AQP4 Expression In Ischemic Stroke

AQP1 And Cerebrospinal Fluid

AQP9 In Cerebral Ischemia

People Also Ask

Conclusion

Suleman Shah

Author

Suleman Shah is a researcher and freelance writer. As a researcher, he has worked with MNS University of Agriculture, Multan (Pakistan) and Texas A & M University (USA). He regularly writes science articles and blogs for science news website immersse.com and open access publishers OA Publishing London and Scientific Times. He loves to keep himself updated on scientific developments and convert these developments into everyday language to update the readers about the developments in the scientific era. His primary research focus is Plant sciences, and he contributed to this field by publishing his research in scientific journals and presenting his work at many Conferences.

Shah graduated from the University of Agriculture Faisalabad (Pakistan) and started his professional carrier with Jaffer Agro Services and later with the Agriculture Department of the Government of Pakistan. His research interest compelled and attracted him to proceed with his carrier in Plant sciences research. So, he started his Ph.D. in Soil Science at MNS University of Agriculture Multan (Pakistan). Later, he started working as a visiting scholar with Texas A&M University (USA).

Shah’s experience with big Open Excess publishers like Springers, Frontiers, MDPI, etc., testified to his belief in Open Access as a barrier-removing mechanism between researchers and the readers of their research. Shah believes that Open Access is revolutionizing the publication process and benefitting research in all fields.

Han Ju

Reviewer

Hello! I'm Han Ju, the heart behind World Wide Journals. My life is a unique tapestry woven from the threads of news, spirituality, and science, enriched by melodies from my guitar. Raised amidst tales of the ancient and the arcane, I developed a keen eye for the stories that truly matter. Through my work, I seek to bridge the seen with the unseen, marrying the rigor of science with the depth of spirituality.

Each article at World Wide Journals is a piece of this ongoing quest, blending analysis with personal reflection. Whether exploring quantum frontiers or strumming chords under the stars, my aim is to inspire and provoke thought, inviting you into a world where every discovery is a note in the grand symphony of existence.

Welcome aboard this journey of insight and exploration, where curiosity leads and music guides.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles